What system levers can tell you about prioritization

System levers and concept material drawn directly from: Thinking in Systems: A primer.

What follows will make sense if you have a systems view of the world. Reading the above book will certainly kick that off, but I'll do my best to illustrate the concepts for you. You can self-audit yourself for a systems view with the following questions:

- Do I value the success of my own team over the success of the organization? (really, truly, deep down...)

- In the context of teamwork - are things great inside my team, but not so great when working outside of it?

If we look at the practical application of 'improving a system', we discover there are systemic mechanisms of change (the book calls them 'levers', so I will, too). These levers have logarithmically scaling (for the sake of argument) degrees of effectiveness and difficulty in implementation. Needless to say, the relationship of lever-to-humanity also scales the same way.

The levers are, in ascending (easy to hard) order:- Numbers

- Buffers

- Stock-and-flow structures

- Delays

- Balancing (self-correcting) feedback loops

- Information flows

- Rules

- Self-organization

- Goals

- Paradigms

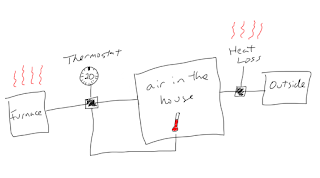

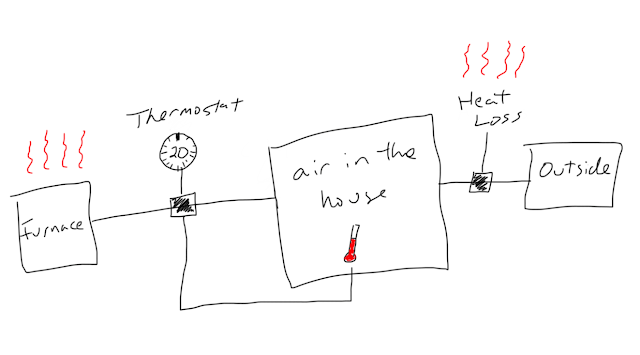

A thermostat in a room is our lever. Adjusting it changes the flow of hot air (number) into a house full of air (buffer). The house full of air at a certain temperature (buffer) is always leaking a certain amount of heat (number). We can visualize it like this:

So without going bananas, we can see our lever in this system is more accurately the thermostat's temperature setting. Changing that number lever up or down modifies the air in the house. The latent heat loss in a building (number) to the outside (buffer) is also a lever. Boost the insulation and seal the cracks - or close an open window! - you get less heat loss (change its number), and so influence the thermostat, but not immediately (delay). The furnace (buffer) has to fire less often because the thermostat's setting (number) changes less often. It's already getting complicated...but wait, there's more!

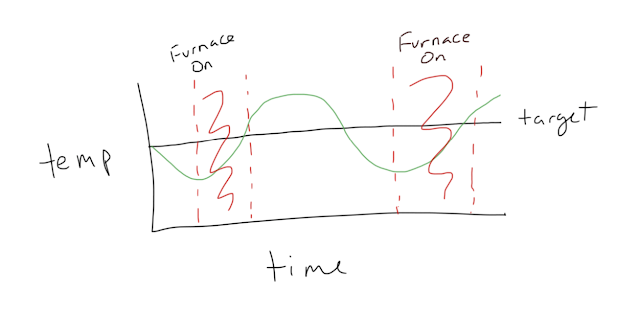

The thermostat in this system creates balance! (called a balancing feedback loop) Setting the target temperature higher or lower changes the system. The thermostat is corking or uncorking the latent heat energy in the furnace and letting it flow into the buffer of air in the house. The heat leaks out, the thermostat notices, and the loop continues.

The key here is that 'by design' the system balances itself - it requires no intervention to maintain that temperature.

Our takeaway here is that by fiddling with numbers, flows, delays, feedback loops - we can certainly make an impact! But at the end of the day the changes are limited to the state of the system as-is. We haven't looked at things like goals and paradigms...here is the end of the levers scale that is far more effective, but similarly far more difficult to accomplish.

Let's look at the goal of this system:

- Use a furnace/thermostat combination to keep the air in a home at a set temperature.

If you change that goal in any way, it will influence everything on 'down' the list of levers. For example:

- Use a furnace/thermostat combination to prevent the air in a home from ever reaching the set temperature.

Further food for thought: consider the impact to the system of an organization if your goals are 'make money at an exponentially increasing rate' - remember, changing the goal changes everything below it!

For clarity, the concept of 'goals' here is based on reality, not espoused. If you have a goal of 'serve the customers' but the reality is 'make money' - it'll show up in the system. (e.g. what gets prioritized or not) In OKR language, you might see, 'Make the customer experience awesome, as measured by 25% larger OCF year over year.' What do your number levers look like with such a system goal? What about information flows?

Finally, the top of the heap are our paradigms - the lenses of understanding through which we interpret the world around us. In our thermostat example, the working paradigms might be:

- The air temperature in the house needs to be different from the outside temperature.

(why not just put on more - or less - clothing?) - We use HVAC systems to fiddle with air characteristics.

(why not a personal breathing device with accompanying suit?) - We need to use HVAC systems as per building code.

(Why not use nanobot drone swarms to heat or cool the air?) - Our comfort is more important than the impact it has on our environment.

You can see why we tend to cap our change ideas at the thermostat!

The paradigm lever also makes visible what adding humans to a system does. It's hard - indeed, impossible - to imagine the full scope of the complexity involved in truly illustrating all that goes into even a simple paradigm like 'comfort is to be pursued'. Consider the challenge we face as we look at the changes we try to make in our workplaces - indeed, the changes required in ourselves.

So back to the point of this post - what system levers can tell us about prioritization is that considering the impact and effort from a systems view offers new insight into why we face friction, why our changes are sometimes ineffective, and what scale of effort is required for true transformation.

When you see problems in your organization, and you set out to fix them, ask these questions:

- Are you considering the effort behind these fixes from a systems perspective?

- Are you attaching too much importance to the small levers?

- Are you disregarding the large levers?

- What are you leaving on the table?

I started the post with the questions about silos vs. systems in a teamwork context. This is why:

In the next post I'll illustrate a simple exercise you can run with change initiative stakeholders that helps make visible the importance of levers. More importantly, the exercise generates shared understanding among those present. Since creating shared understanding is a bedrock task in leadership - any chance to work on it is worth the effort!

Comments

Post a Comment